![]()

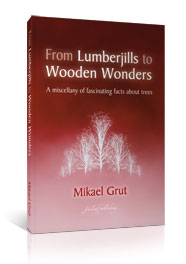

Welcome to my blog. Its purpose is to give, where I can, further information on the entries in my book From Lumberjills to Wooden Wonders [1]. If you disagree with what I say there, do write – debate is good. If you see errors, please inform me – I should know.

If you have interesting entries to contribute, please submit them, and remember to put your name under. For your reference, the book entries under “A” and some of the ones under “B” are on the site http://dl.dropbox.com/u/65432302/lumberjillsSAMPLE.pdf. Your entries could eventually be part of a collection here, accessible to everybody.

Mikael Grut

[1] Mikael Grut: “From Lumberjills to Wooden Wonders. A miscellany of fascinating facts about trees”. Published in 2012 by Fineleaf, Ross-on-Wye, England, www.fineleaf.co.uk, books@fineleaf.co.uk. ISBN 978-1-907741-10-4. Price: £10.95 incl. postage.